An implementation of a protocol called Mimblewimble, which is a different way to design a blockchain that was anonymously shared in July 2016.

But how is it different from all the other blockchain designs? MWC’s blockchain is really just a single big transaction. This doesn’t make any sense when you first hear it and seems hard to believe at first, but it turns out to be true. We will explore the world of MWC transactions and how they fit together to form a blockchain.

We will simplify some things intentionally to not get you lost on the details, but we promise it won’t be anything too important. The purpose is to explain the grand picture of the protocol and why it is considered by many cryptographers as the most interesting blockchain design to date.

Intro to Confidential Transactions

MWC builds on a lot of previous research which was done in the Bitcoin space. It uses Confidential Transactions at the core of its design which means that all the amounts are blinded. But it doesn’t use the idea as was originally described in the paper, it instead improves on it. An output in a Confidential Transaction is described as a bunch of random characters and numbers to anyone observing it e.g. 09fe4d4d2aa97ba9c52ea494c967bddb12d1e394bbe91692e53 .

What Mimblewimble does differently is that this random sequence holds the information about both the amount and the owner, but does not reveal either of them - in the original paper, it only holds the information about the amounts. There is no notion of a script or an address in Mimblewimble, an output is just a single random sequence of characters. The main idea behind Confidential Transactions is that it proves that the sum of the input amounts minus the sum of the output amounts is zero but it does so in a way that does not reveal the amounts - this balance between the sums must also hold for every Bitcoin transactions (we’re ignoring the fees for simplicity). Bitcoin proves this by having the amounts public so anyone can check the transaction is well balanced and no new money was created. We won’t go into the cryptography behind Confidential Transactions, the important thing to know is that it proves the balance of the transaction is valid without revealing the amounts. Now that we know what the outputs look like, let’s check what a MWC transaction looks like.

There’s some annoyance when proving Σinput.amount - Σoutput.amount = 0 without revealing the amounts, because it is possible that someone would try to encode in this random sequence a negative amount which would allow the creation of coins out of thin air. To prevent this, we need to prove that the amount the output hides is within a certain range of nonnegative numbers, but we must do so in a way that does not reveal the amount itself. This is achieved with something that is referred to as a zero knowledge rangeproof and each output comes with this rangeproof. We won’t be talking about rangeproofs in this post because they don’t help with the understanding of Mimblewimble, it’s enough to know that they need to be included due to some details.

MWC transaction

A transaction in MWC is composed of 3 sets. A set of inputs, a set of outputs and a set of kernels. We are familiar with the idea of an output from Bitcoin already - it can be thought of as a pile of money that is publicly seen and has an owner. An input is really just an output that is being spent, the representation is the same. As mentioned in the previous section, the outputs (and hence also inputs) don’t show their amounts so they can be thought as bags of money where the amount is not visible to anyone. The kernels is something that was introduced in the Mimblewimble whitepaper, but the author called it the Excess in the paper. We don’t really need to know what a kernel looks like, we only need to know that it serves as a proof that the transaction is valid. A kernel of the transaction:

- proves the transaction does not lose any coins or create new ones out of thin air - Σinput.amount - Σoutput.amount = 0

- proves the authenticity of the transaction, meaning that all the input and output owners agreed with this transaction

This is quite neat, we have a single thing called a kernel that takes care of all the important things in a transaction!

A kernel is a very small piece of data ~100 bytes that contains only a random curve point and a signature. We don’t need to know these details in order to understand the main idea behind Mimblewimble and MWC, so we’ve skipped the internals, but this single 100 bytes of data proves both non-inflation and authenticity of the transaction!

As we can see from the picture, this is a transaction that has a single input, two outputs and a kernel that pays 0.011 fee. A person that observed this transaction can’t tell who the sender or the receiver is or what amounts any of the inputs and outputs hold. They could know this if they had some metadata about the inputs and outputs, but it’s impossible to tell just by looking at the transaction.

Transaction aggregation

AMWC allows us to concatenate two transaction to obtain a single transaction. We call this transaction aggregation, but is known in the Bitcoin space as a CoinJoin. This Coinjoin is more powerful than the one on the Bitcoin network because you don’t need to match the amounts since they’re not visible and it does not require the transaction owners to get together and do the CoinJoin interactively. This means that anyone who sees two MWC transactions can just concatenate them together into a single transaction. The transaction once aggregated, can’t be deaggregated by anyone that has not seen the transactions prior to the aggregation.

Let’s say we have the following two transactions

We can aggregate them to obtain a new transaction that cannot be deaggregated into two transactions (we can do it since we have seen the transactions prior to their aggregation).

We have a single transaction now. Notice that the inputs, outputs and kernels have shuffled their order a bit. This is because they are sorted ascendingly in order to prevent guessing which could be a part of the same transaction e.g. if we simply added them at the end, then the last two outputs and the last input would likely be from the same transaction. We also have two kernels now and this is fine because a transaction has a set of kernels and when we aggregate two valid transactions, their kernels will serve as a proof that the transaction is valid - we need both kernels to prove the validity of this aggregated transaction. Since the result is just another MWC transaction, we can aggregate it with a new transaction to get an even bigger transaction - we can repeat this aggregation process as many times as we like.

This allows us to aggregate all the transactions in a block into a single transaction. We no longer need to represent the block as a sequence of transactions, we can just say that it contains a set of inputs, a set of outputs and a set of kernels. The block itself is just a couple of headers and a single transaction!

Transaction Cut-through

In Bitcoin, the new nodes joining the network need to download the history of all transactions and replay them locally to reproduce the state of the ledger. Mimblewimble and MWC improve on this. Let’s take a look at what happens when a transaction is made on this new blockchain design.

Let’s say we have the following transaction

Let’s now consider another transaction that spends one of the outputs from the first transaction

We now aggregate the two transactions together to get

Huh? Not what we expected is it? Where did the purple input and output disappear?! Turns out that when an output is spent, we can delete the matching input and output and forget about them all together as if they never existed and the transaction is still valid! This means that we can spend and forget even before the transaction gets registered on the blockchain. This process of reducing a transaction to a simpler one where we remove the matching inputs and outputs is called transaction cut-through and was first introduced on Bitcointalk forum by Greg Maxwell. We have already learned that the block is a single transaction so we can forget the existence of the matching inputs and outputs before we publish the block, and in fact, MWC does not consider a block valid unless a cut-through has been done.

And we have finally arrived at the moment where we’ll see the real magic.

The whole blockchain is a transaction

As we mentioned at the beginning, the whole MWC blockchain is a single big transaction. We already know that each block is a single transaction and that any two transactions can be aggregated together. This means we can just aggregate all the block transactions into a single big transaction. But since this transaction contains the whole blockchain history, it means that every spent input in a transaction is an output created earlier. This means that every spent output in the history of the chain can be completely forgotten as if it never existed, we just need to keep the kernels for all the transactions! If we were to validate this cut-through transaction that contained the whole blockchain history, it would not be valid because each block creates new MWC coins as a reward for miners. But if we take into account that the chain created height reward MWC coins, then it balances out. This whole blockchain transaction is also a check that the total supply is exactly height reward MWC. Since a blockchain validation in MWC is nothing more than a transaction validation, this means that this big blockchain transaction is exactly the data a new node needs in order to sync to the network. The initial sync is nothing more than the download of this one big transaction and the validation of it

We have colored the outputs that have not been spent yet with a more solid color. After we do the cut-through on the whole blockchain we get the following transaction

and voilá! is again a valid transaction.

As mentioned above, when we do the cut-through on the transaction obtained from aggregating all the historical transactions, we are left with no inputs, all the unspent outputs in the outputs set and all the kernels from the past transactions in the kernels set. As mentioned above, since we know that each block creates NEW MWC, we can validate the whole transaction supply with a simple formula Σ utxo = Σ kernel + height reward MWC H which checks that the transaction is valid if we assume that we had height number of blocks - at this point, it is not expected you understand the formula from this post because we did not dive into the cryptography, the intent is to show the elegance of the protocol. This blockchain transaction being valid is also a proof that all the historical transactions were valid and authenticated. This simplicity of the protocol is also aligned with the trust minimization idea because we achieve a lot without needing to rely on any new and fancy crypto, in fact Mimblewimble relies on the same cryptographic assumptions as Bitcoin.

Comparison to other privacy enhancing technologies

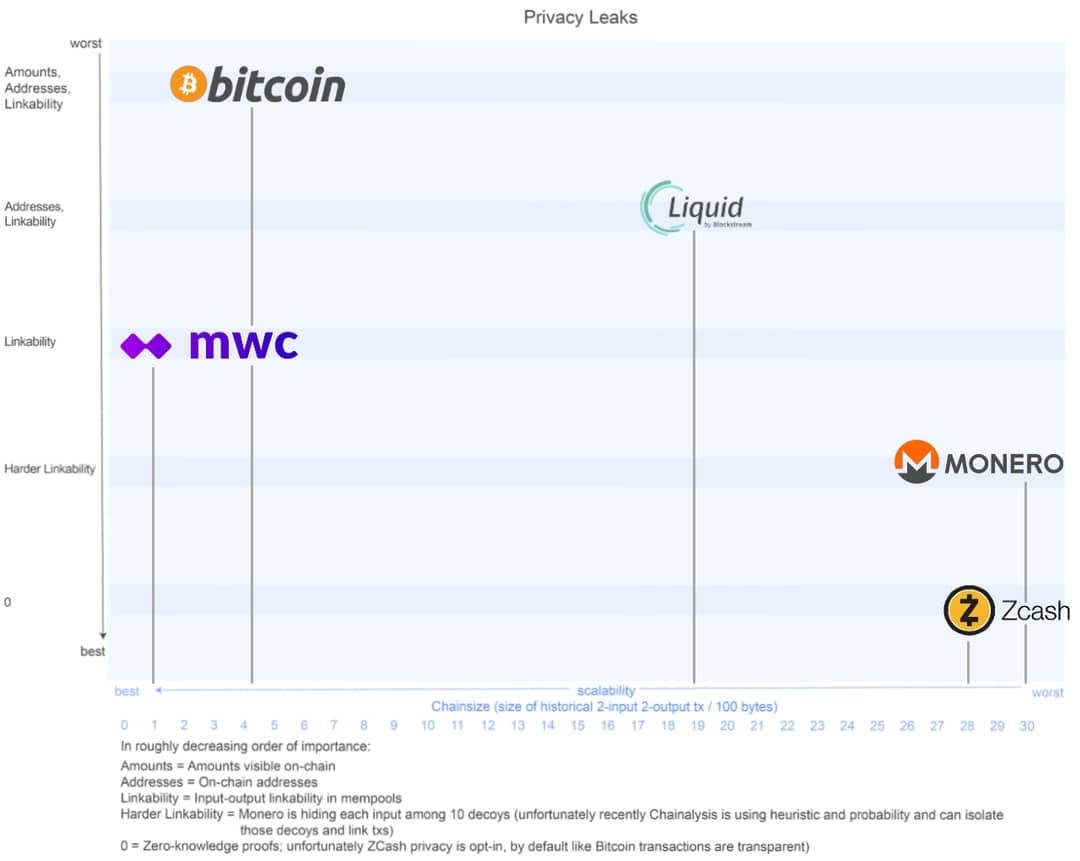

There are different technologies that try to achieve a better privacy compared to Bitcoin. Most of the technologies that do so come at a cost of increased chain size. Mimblewimble is the first approach that improves the privacy of the base layer without worsening its scalability. In fact, we end up with a blockchain that is smaller in size than Bitcoin! Here’s a chart comparing different privacy technologies and showing how they affect the size of the blockchain.

The only information that Mimblewimble leaks is the input-output linkability. Mimblewimble has two tools at disposal that could help obfuscate the transaction graph. The first is the ability to freely aggregate transactions which opens up possibilities for services that aggregate the transactions. Given enough volume, Mimblewimble could provide a similar decoy privacy as RingCT, but with some required trust towards the service - hopefully in the future there will be trustless alternatives available. The other tool that still needs research is the possibility of adding decoy outputs to a transaction. These decoy outputs come for free as they don’t add any size to the blockchain in the long term because they are a special case that does not need the proof to be expressed as a kernel that needs to stay on the chain.

To read about the original proposed design in detail, read the original Mimblewimble whitepaper.

For more information about the MimbleWimble protocol watch those video:

MimbleWimble with Andrew Poelstra

Mimblewimble and Scriptless Scripts with Andrew Poelstra